About Belly Dancing in the USA

Looking out over what American belly dancers are doing and teaching, I see four major types of dance, each with several subsets: Turkish, Egyptian, Ethno-Fusion or World, and American Tribal. We'll take each one and have a little look at what makes it special and how you can tell which one you are seeing.

Turkish Belly Dance

Most people think they can tell Turkish belly dance by the sequence of the show. Fast-Slow-Fast-Slow-Drum Solo-Fast (and/or 9/8). After that, they set out to define the style by describing the moves in a typical nightclub show: a veiled female soloist playing zills enters to an up-tempo song in either 4/4 or 2/4, dances lyrically to a rhumba while undraping and manipulating her veils, sheds the veil and segues into a second fast song (again either 2/4 or 4/4), often inviting audience members to dance with her. The music changes to the slow, emphatic, sensual beat of a Chifte Telli. The dancer responds with undulations, sinuous armwork, and the like, often embellished by flutters and vibrations and perhaps a descent to the floor. A drum solo featuring shimmies and sharp hipwork follows. She concludes with either a Turkish 9/8, often with skirtwork, an up-tempo tuta, or both. The rhumba, the long Chifte Telli, and the Karsilama (a regional dance with Roma and folk origins) are uniquely Turkish. For a cognoscenti, however, the "Turkish" part has less to do with the sequence of songs than with travel, footwork, and body angles. The dancer is free to travel around the room. More importantly, much of her hip movement is generated with her feet. Her steps, especially in the fast segments, feature elaborate and quick weight shifts, fast plies and hops, and heel-toe combinations. And many of the hip moves start with or accent a hip lift. These steps are drawn from Turkish folk dance. As for the dancer's body position, steps in place may be done with a backward tilt; during travel steps, the upper body is often leaning or bending away from the direction of travel, and small kicks may finish with a small pull into the pelvis that angles the torso slightly forward. Footwork is generally highly patterned and complex, with tempos that are generally quit fast. For instance, a local rising star I know took what she thought of as a standard Turkish show into a Turkish restaurant. After the show, the Turkish owner said to her, "Stick with the fast music-- less of that slow stuff, please."

Egyptian Belly Dance

The essential Egyptian style of dance is rooted--the dancer works in place, performing controlled isolated hip movements often accompanied by undulations and/or shimmies or vibrations. Control, control, and more control plus precision: those are the hallmarks of Egyptian dance. Accents tend to be down, and the overall feel or tone, is earthly and sensuous. Hip drops accent the beat. The dancer's movements are clear, clean, and exquisitely defined; she is playing the music with her torso. Western travelers used to call raqs sharki "muscle dancing," referring to both the dancer's control of her fine muscle movements and her use of all the muscles in her torso, including back and belly. Footwork and armwork are minimized; hips are torso are all. And of course the music is Egyptian or Arabic: composed, stylized, and structured. Frequent abrupt changes in tempo and tone within each piece require the dancer to know her music, to be able to hit the accents and stops exactly, and to anticipate and react to changes in style and mood. This places more importance on set choreography. Choreography also helps the dancer provide enough variety in her routine to demonstrate her expertise and range as well as to keep the audience involved in her performance. Long, no-tempo instrumental solos or taxims ask for deep emotional expression and subtle, controlled movement. To be able to respond to the challenge of a taxim, a dancer must have full command of the idiom and be intensely engaged with the music. There is nowhere to hide. A second form of Egyptian dance can be called "show biz folkloric." Using folk steps, props, and traditional music, the dancer performs highly stylized versions of country or regional folk dances. While these dances have their own legitimacy as stage pieces and have come to be expected by Egyptian audiences, they have about as much in common with their folk roots as the ballet sequences in Oklahoma have with a barn dance: inspiration, reference, and homage.

Ethno-Fusion or World Belly Dance

This style is very hard to describe, although you know it when you see it. The dancer takes elements from different forms including other ethnic dances, and incorporates them into her fundamental belly dance performances to make a highly personal synthesis. The music can be traditional or modern. The success of the fusion depends entirely on the taste and skill of the performer. A genius such as Elena Lentini creates something wonderful and new; a less-talented dancer can commit a crime against art.

American Tribal Belly Dance

At last, something new under the sun! American Tribal started on the West Coast and is quickly spreading around the world. It's less about the music and pure dance than it is about community and feminine strength, beauty, and power. The roots of the style are in North African tribal dance combined with belly dance moves, especially large undulations and shimmies. Movements are strong, originating deep in the torso. The focus is more on the group than on the individual. A soloist emerges from the group, dances, and is reabsorbed, to be followed by another. The group breaks into smaller units and flows back together. Invisible cues signal shifts. In their distinctive costumes and facial tattoos, the dancers become anonymous iconic females independent of time and place.

Describing ATB cannot do it justice. I believe it's something you either "get" or you don't. ATB seems less dependent on the audience for inspiration than on its own group dynamics. It is a profound way of expressing female connectedness.

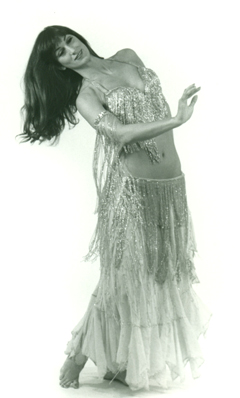

This is an article about Belly Dancing written by Stella of New York.